We are now in the final stages of the reporting season for the first quarter of 2025 for companies with December 31 year ends. We usually find the regular rhythm of corporate earnings a useful cue for stock-taking. This year is not like normal years since the last month has been dominated by the tariff drama which rendered actual earnings trends irrelevant, or at least severely deprioritised in terms of market attention. The recently announced China ‘pause’, while it left trade barriers tighter than pre-April 2 levels, represents a possibly permanent end to the trade discussions and a shift in focus to domestic US fiscal issues. This expectation explains stock prices being broadly above their pre-April 2 levels despite material cuts to sell-side earnings expectations for 2025. While this looks paradoxical, there is a logic to it: before April 2 the administration’s desires for tariffs and a new Fed president were known but unexplored, whereas both have since been put ‘in a box’, hence the market is willing to pay a higher earnings multiple[i] as it is looking through to better 2026 earnings with reduced risk of a surprise thunderbolt from above (Washington DC).

The Q1 earnings are an interesting counterpoint as they pre-date the Liberation Day drama, as companies closed their books on March 31. While there was an understandable focus on post-quarter trends and forward guidance, what we found most useful were the trends which are likely to persist even if tariffs are entirely rolled back. We focus on the US consumer as he or she represents the most important swing factor for global personal consumption, and perhaps the most important single motor of the global economy. The consumer has been under pressure for a couple of years now from the severe inflationary pulse of 2022-2023. Our expectation was that given moderating inflation and sustained decent household income growth, ‘nature would heal itself’ as consumers and small businesses repaired their balance sheets and resumed normal consumption behaviour. This has not materialised as things got incrementally tougher. In the universe of large consumer staples companies we track, US organic sales slipped into decline during the quarter. Scanner data aggregated by Nielsen also decelerated, though not as severely, which we think reflects increased share shifting to private label brands. McDonald’s called out a 10% decline in traffic from lower-income consumers, as well as a concerning decline in middle-income traffic growth, indicating growing stress further up the wealth ladder. We do not think that this is a result of consumer behaviour changing due to GLP-1s or clean eating trends, as softness was broad and covered basically all household and personal care categories. Non-staples areas of consumer spend also got worse in the quarter with lower end hotels and ‘back of the bus’ domestic air travel deteriorating and continuing to lag more premium options in lodging and flights.

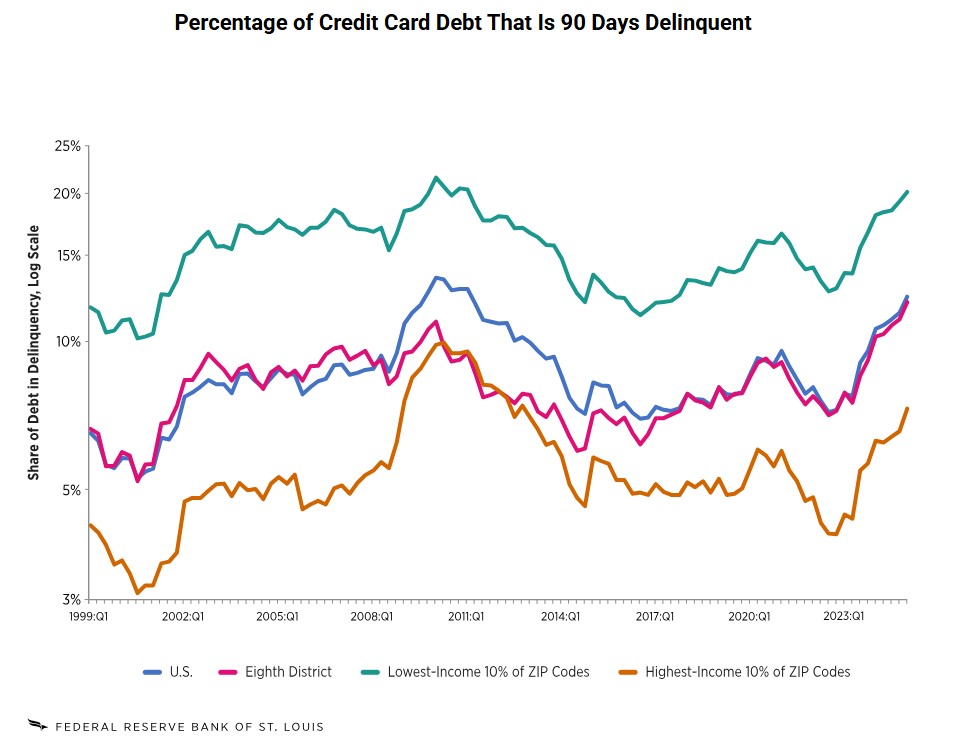

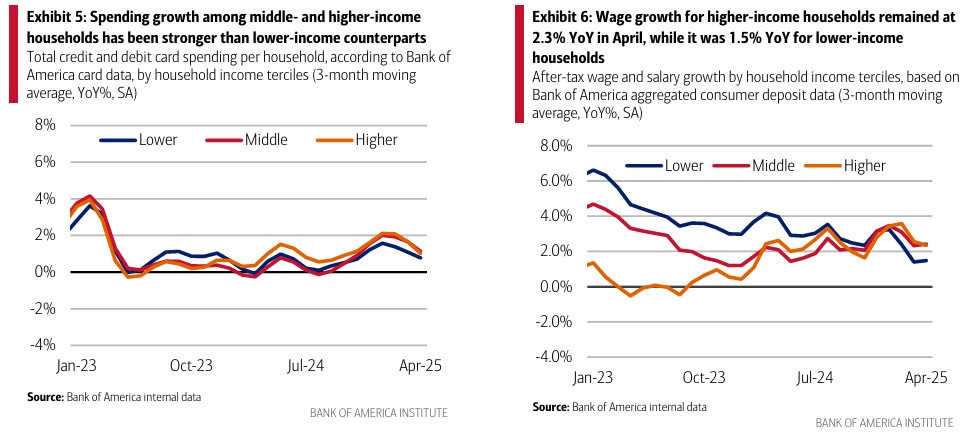

Broad economy indicators like Mastercard and Visa disclosure on payments volume, Bank of America data on spending by their depositors, and federal agency surveys continue to be healthier than those for consumer goods and for lower end consumer services. However, the BofA’s picture of the lower end consumer corroborates the other data we are looking at. Likewise, data on credit card delinquencies and student loan borrowers indicate growing stress disproportionately on specific demographics.

To be clear, we are absolutely not prophesying a recession or a bear market, rather we are stressing an important and neglected trend which has been overshadowed by geopolitical histrionics. At a high level, the US looks great, with low unemployment, strong productivity growth, and (until tariffs) strong corporate confidence and gradually improving bank loan growth. There is therefore a temptation to say that these consumers can be written off as unnecessary for corporate earnings, but we think it will be quite hard to sustain double-digit corporate earnings growth if the fortunes of the consumers who in aggregate make up about 45% of consumer expenditure (using BLS estimates) and therefore 32% of GDP continue to weaken.

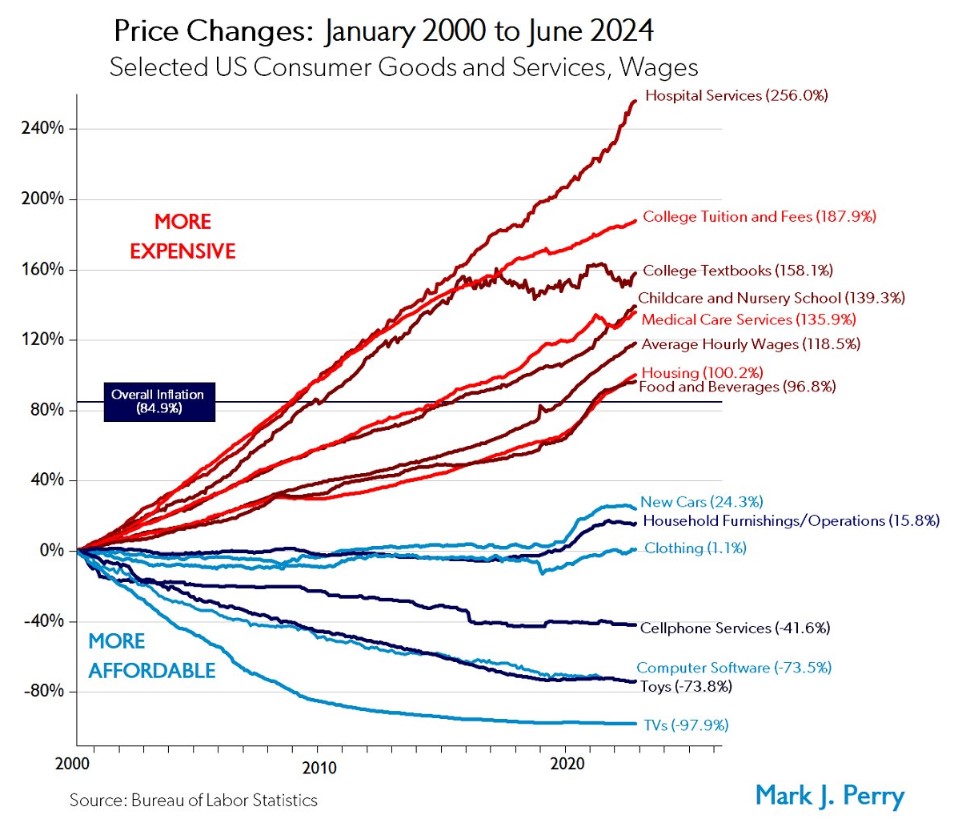

It is hard to see unemployment improving meaningfully from here, as it is still very close to its long-term lower bound. Nor do we see wage growth accelerating absent another inflationary surge, as so far strong productivity growth has not prevented deceleration of wage growth. While there are hopes of large US tax cuts, these hopes are closely twinned with expectations for large cuts to federal aid programmes like Medicaid which are likely to offset tax savings, particularly further down the income ladder. As we have noted before, consumer purchasing power has probably been drained away from staples by high inflation in non-traded services like insurance and rent, plus big swings in commodity goods like gas (petrol) and eggs. There is good news for inflation in lower gas prices, but on the other hand some level of incrementally higher tariffs is here to stay, which will probably diminish the powerful deflationary impulse from cheaper imported goods, shown here in AEI’s ‘chart of the century’.

What does this all mean for our portfolio? While we keep an eye on macroeconomic trends, as discussed above, it is absolutely not about trading actively against an expected macro outcome, but rather so we have a yardstick for measuring portfolio company progress. While it is tempting, depending on one’s temperament, to dump staples or cyclicals at this point, we think it is the wrong debate to have, and certainly not one where we will have a differentiated view. We are not reducing or adding to cyclically exposed companies, and continue to retain a mixture of names with idiosyncratic cyclical exposure like Informa, Amadeus, Experian, Marsh McLennan, and Booking, as well as ones with more defensive characteristics like Heineken, Relx, Jack Henry, and Johnson & Johnson. The most important common thread is not low defensiveness or high gearing into GDP growth per se, but the ability to grow market share over time through cycles thanks to an increasingly superior and desirable product.

Where we are invested in cyclical companies, they tend to the best player in their market and to be revenue-critical to their enterprise clients. Even companies which are ostensibly consumer-facing like Booking and L’Oreal are vital partners to their enterprise partners – in this case, hotel owners and retailers – as their brands and networks drive high margin traffic to fixed cost locations which need to keep the cash flowing in to pay shareholders and service leases. To us, the most important takeaway from the analysis above is that earnings growth is likely to be tougher and more idiosyncratic than in the recent past, which reinforces our desire to double down on companies with differentiated and well invested products. Our commitment to managing valuation risk is unchanged and remains indifferent to macroeconomic context; we will always work hard to ensure that our portfolios enjoy a margin of safety, irrespective of market sentiment, for the same reason that responsible ship captains keep servicing their lifeboats regardless of the weather.

Where we have made changes so far it has been focused on these quality upgrades. We have added two businesses, as discussed in earlier updates, which sell to a consumer base (New York Times and Booking). In the case of Booking, it was a straight swap for Airbnb, as we had concluded that Booking’s superior investment and diversification made it both more defensive and more likely to gain total lodging share over time – it is very early days, but so far this thesis appears to be bearing up. New York Times again is a well-invested, category defining franchise, with a good history of execution in changing its business model and keeping focused on its ‘true north’ of business excellence in a market which has been utterly upended by the Internet.

Our portfolio so far this quarter has reported 7% revenue growth and 14% earnings per share[ii] (EPS) growth, markedly ahead of the pace set by the constituents of the major stock indices we track. We are particularly pleased by this performance in the context of the data above on the lower-income consumer, which has made the economy quite dependent on the cohort of higher-income consumers and capex boom on server capacity. In an unbalanced economy, we are continuing to see good growth from a more balanced portfolio. While the gap between portfolio growth and index growth is reassuring, it is less important than another gap which we can only track retrospectively, which is the long-term difference between fundamental compounding by our portfolios and by the wider universe of investable companies. This gap is absolutely key to our strategy. If it holds for long enough, and we are successful in avoiding egregious overvaluation, the portfolio should deliver a superior total shareholder return over time. All macroeconomic analysis like that shared above is with the fundamental purpose of tracking progress towards this goal.

On a final note, portfolio valuation remains attractive in relative and absolute terms despite of its outperformance of the broader index since the start of the year. As a reminder, we build our portfolios based on our calculation of internal rates of return based on fundamental models, but we also track conventional methods like free cash flow (FCF) yield[iii] which are comparable to the broader market. The portfolio closed April 2025 on a 4.1% FCF yield [Source: Bloomberg Estimates] vs the MSCI World which was on a 3.9% yield. Given superior portfolio growth, these jaws yawn wider if you roll the tape forward to look at CY25 and CY26 earnings. We remain optimistic for the year ahead, and all the years after it, and look forward to sharing more with you later this year about areas we are focusing our research efforts.

James, Chris, Cristina, Gurinder, and the Evenlode Team