As selectors of companies on our clients’ behalf we are keen to report on how the ones in the portfolios we manage are performing on the ground. Our colleagues on the IFSL Evenlode Income and IFSL Evenlode Global Equity strategies have done just that recently, as indeed we did from a Global Income perspective a month ago[i]. We have also been keen to note just what good value those companies seem to be trading at in the market, a situation that has not changed materially over recent weeks. We haven’t been alone in observing that many high-quality businesses have been underperforming in the market, leading to those compelling valuations. Various articles, comments and analyses suggest similar, often looking at an off-the-shelf index that categorises companies on the basis of their financial characteristics versus a broad market index[ii].

Articles stating that ‘quality has underperformed’ certainly ring true with our lived experience as investors that look for market leading companies with solid financials and dividend-growing capabilities. Thinking about where the action has been in the market it kind of makes sense. Banks and Capital Goods companies that have historically generated low returns on capital have been on the up, as well as unprofitable technology companies.

But it only kind of makes sense because whilst directionally we might expect solid businesses to underperform in a robust economy, the magnitude of the differential for certain businesses has been dramatic. The global economy is patchy rather than robust. Also, broad-brush statements about quality’s performance depend on what index is examined, and over what time period. Bringing in questions of valuation make the whole picture a bit perplexing, as we’ll touch on below.

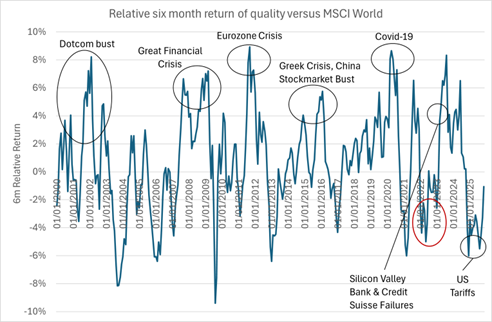

Taking the MSCI World Index as a guide illustrates some of the challenges in the narrative around quality. The chart below shows the six-month relative return of the ‘quality’ sub index, compared to the headline MSCI World Index. Whilst it’s as noisy as any other time series in financial markets, it does seem that on the whole quality’s outperformance since the turn of the Millennium has come in times of economic or market stress.

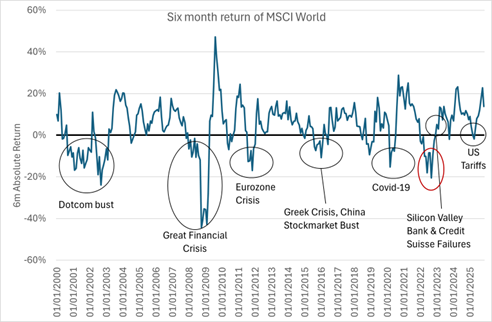

Casting the same episodes in financial history on a chart of the rolling six-month absolute return of the MSCI World Index confirms that the outperformance of quality is indeed generally when equity markets are more challenged.

But more recently something different appears to be happening. The time circled in red on both charts represents a sell-off, particularly in Information Technology companies, in 2022. There were concerns at that time around rising inflation and interest rates, but also about valuations that had expanded through the coronavirus pandemic. Once that had bottomed and the mini financial crisis of spring 2023 had been stabilised, there has not been much market stress despite the occasional headline. Even the tariff-related volatility barely features as a negative on the chart above in historical terms. It was, though, a recent low, and in that brief period quality underperformed, bucking the defensive characteristics previously shown. The sub-index’s relative performance has recovered in the market rebound.

Quality also underperformed in the 2022 sell-off. It doesn’t take too much analysis to figure out that the quality index has become dominated by the same technology companies that dominate the broader market. The market action would suggest so, and a quick use of your favourite search engine (no AI required) finds the Magnificent 7[iii] atop quality indices. This, then, brings us to the much-discussed question of valuation.

One would normally expect to pay up for quality, and indeed this is the case at the current time. At the time of writing the price/earnings multiple[iv] on the MSCI World Index is about three ‘turns’ below that of its quality sub-index. Going back ten years, that figure was two turns, so quality has got a bit more expensive relatively speaking. But the absolute figures are important, or at least they should be. Ten years ago the MSCI World Index traded at a multiple of 18x, now it is 24x. The gap between quality and the rest is in fact higher, because the ‘quality’ sub-index included in the broad index.

To say it again, we have been very keen in recent times to note how the Evenlode portfolios look to be trading at unusually attractive valuations, which runs counter to the quality narrative above. We are able to achieve this because we don’t, of course, invest in indices. We invest our clients’ capital in companies, and we can select ones that meet our quality criteria but also trade at sensible valuations. The businesses in the Evenlode Global Dividend portfolio are trading at a multiple of 18x as a weighted average, a figure that has a distinctly 2015 air about it. In fact, better than 2015, because 18x would have been in line with the broad index back then, and our collection of companies exhibits quality characteristics across many financial and qualitative dimensions.

The makeup of an index or fund thus matters, and matters even more if valuation is taken into consideration, as we believe it should do as active investors looking to manage and balance long term risk and return. Further, indices that have different entrance criteria can prove to switch behaviour between different market regimes.

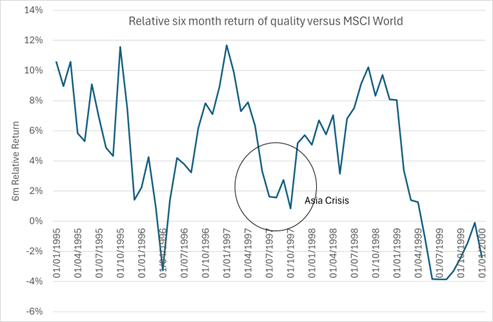

The previous charts start at the turn of the millennium. That’s not just a memorable moment in time because 2000 is a round number, it’s also a memorable time in stock market history. The crescendo of the dotcom boom was just about to turn the other way, and the quality index was hitting its stride in relative terms. Rewind the clock a little further and we see that quality did pretty well prior to the bursting of the bubble, but interestingly less well in a relative sense when there was an economic wobble in the form of the Asia Crisis. That was another time when markets were roaring, valuations were high, and perhaps some of the usual relationships between indices with differing characteristics

broke down.

Quality as an idea has shown itself to be valuable over long periods of time. In these periodically strange sorts of markets, as we are undoubtedly in now, we think it is particularly important to look beyond the style and focus on its application to individual companies. We hope you forgive the diversion to discuss market indices, but we think it serves to highlight the challenges of piecing together market narratives and indeed choosing benchmarks.

Neat narratives ignore the messy reality of markets where differing actors bid prices up and down for variant reasons, and correlations that seem plausible and even explanatory can change or break down through time.

Our focus is on identifying great businesses and assessing their valuations, and whilst not easy, is at least a simpler proposition. The changes in market regime can create opportunities. At the moment at the granular stock level the market is, despite the expensive level of both the broad and ‘quality’ indices, throwing up some interesting propositions that may find their way into the portfolio.

Ben Peters and Rob Strachan

28 November 2025