Hopes at the start of the year of a transient period of Covid-related inflationary pressure before a return to business-as-usual seem a distant memory. The implications of the war in Ukraine have firmly taken hold, bringing spiralling energy and food price inflation globally. At home the inevitable threat of wage inflation has crept into tight labour markets post Brexit, fuelling further recessionary concern, and political instability has left us all feeling slightly rudderless.

This backdrop is argued by some as a challenge to both country level and company ESG focus, threatening a reversion to the long grass for systemic problem solving and a return to previously held views that ESG management is merely a feel-good factor for more buoyant times.

We do not see this.

At a country level it is true the Ukraine crisis has highlighted the need for energy security, re-opening debates around coal use and new fossil fuel exploration and production. However, arrived climate risk exacerbating fuel demand and crop failures is keeping the eye on the prize of Net Zero and, if anything, in Europe the need to transition to clean energy faster than planned has been reinforced.

At the company level, we consider the management of E, S, and G issues as fundamental quality indicators. Whether looking at how employment brands and talent management correlate with shifting employee preferences, or at company investment in digitization, automation and resource efficiency, we see strong governance guiding long-term decision making to capture and retain competitive advantage and new opportunities.

By way of example, the first half has seen ongoing debate about structural changes in supply chain management. Companies focussed purely on short-term financial optimisation have been caught out chasing cheap production and just-in-time stock levels. Their long supply chains from regions such as China, became unreliable during Covid and are now more expensive due to increased energy costs. Conversely, those with high customer focus, committed to delivery, recognised the shift to near-shoring and just-in-case stock levels earlier, improving their resilience, environmental impact, and even social impact, given the higher supply chain visibility in better regulated regions.

Change forces imply a continuing shift away from cheap consumerism towards a more sustainable model, and we note the best managements have been positioning through their investment and decision making for some time now, building ESG management capabilities as a source of competitive strength.

On a final note, for the cynics who consider the cost of the regulatory trajectory in Europe and UK to have gone too far in relation to sustainability, it may be worth considering some of the competitive advantages we have been garnering.

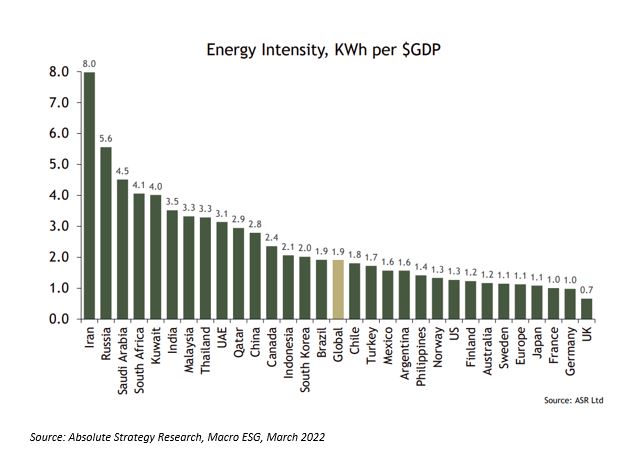

For example, energy intensity is a measure of the energy inefficiency of an economy. It is calculated as units of energy per unit of GDP. High energy intensities indicate a high price or cost of converting energy into GDP. Low energy intensity indicates a lower price or cost of converting energy into GDP.

The following chart is interesting in this regard:

Sally Clifton

Head of Responsible Investing